In light of Coronavirus, a pandemic in the shadows of the Spanish Flu and Black Plague, I became interested in art that surfaced from these viral disruptions. So, how will art morph during our recent global isolation and unified cause of death?

After months of lockdown, we are being released back into the green phase once again unified in peace, marching, and protest for equality under the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Perhaps this was the universal intention to reflect and gather for a greater purpose, a catalyst for change.

Black Plague Art: Mourning the Dead

Sedlec Ossuary:

Sedlec Ossuary known as the “Bone Church” in Kutná Hora is an hour train ride east from Prague.

The Baroque, 14th century, a Catholic church built atop souvenir soil from Jerusalem, rumored to be where Jesus was crucified, made it a desirable place to be buried in Bohemia. During the Black Death, many thousands pilgrimaged here as their final resting place.

Down in the belly of the church, a local woodcarver, František Rint, was commissioned in 1870 to design macabre art with more than 40,000 bones from the overpopulated cemetery, using almost the entire bone structure of the human body.

Although this art is not created during the plague, the artist’s medium was human remains that lived through one. Rint created chandeliers, pyramids of skulls, a coat of arms, and his signature hanging by the staircase made from the bleached bones of plagued skeletons.

Today, (well not currently) visitors can stand under wreaths of the dead, view sculptures of bone behind beeping gates, and in a more disturbing scene take selfies with the skulls. (Current update: no photos allowed anymore)

My poem for a writing class October 2017:

Bare Skulls & Naked Trees: Sedlec Ossuary

Skulls hang from the arched doorways.

Shadows like silhouettes of fleshed faces in top hats.

Were they farmers, lovers, men of God?

Differences fused in a pilgrimage from plague.

All feared illness, death, and God. Stacked bones of

illness, death, and God. Chandeliers of illness, death, and

God. Walking back to the train, the naked trees looked warm for October.

I felt flesh on my cold limbs with no fears to fuse.

Dance of Death:

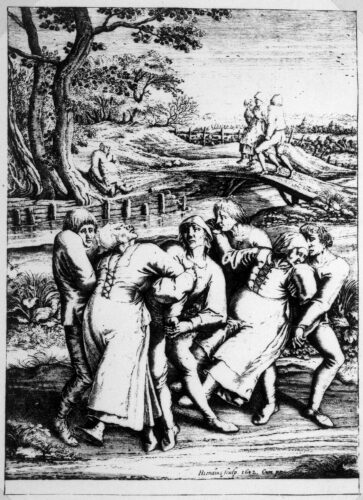

During the rampage of the Black Death in the 14th century most artistic ventures, namely architecture and fresco painting, came to a halt reminiscent of our sudden lockdown. But the aftermath trauma blossomed to what many scholars coined as depictions of ‘Danse Macabre’ French for ‘Dance of Death.’

Sardis Medrano-Cabral posting for Montana State University, mentions that these rituals were probably “first performed, then poeticized, then finally painted.”

However, many also comment on its connection to ongoing war and royal assassination. Nonetheless, sudden death is at the forefront.

Intricately painted murals storied the millions of bacterial deaths and the increased terror of demise by painting skeletons in a circle of merriment.

I narrowed in to the ‘Dance of Death’ because (it’s my f***ing blog) my connection to movement, especially in healing grief has been innate. Unlike those of plague past, I never danced in the fear of God, rather praise for life.

The conjoining of living and skeletal figures symbolize cherishing life and understanding its ephemeral and sudden end. Often depicted with stoic kings and royalty, this perceives that no class or privilege is immune to the death of disease.

Perhaps these paintings are distant dreams of true episodes of manic dancing. Before the plague and throughout the next centuries, detailed accounts sprang up of people dancing en masse through quiet villages along the Rhine river in spastic, uncontrollable movements.

Many joined until they died from exhaustion or broke their ribs. It is unclear what caused these marathons, known as St. Vitus Dance.

Priests blamed curses from St. Vitus as punishments for sin or demons trapped in human flesh, supernatural warfare that many became possessed within a psychological trance.

Historians blame collective stress and mass hysteria from famine, war, and plague or the possibility of Ergot poisoning from consuming rye which possesses psychedelic tendencies, the same poisoning hypothesis often connected with the Salem Witch Trials.

To counter and heal these delusions, medieval officials with good intentions hired musicians to uplift the dancers; this only caused more people to join and episodes to last longer.

Most notably recorded is the story of Frau Troffea who began her epic, months-long marathon encouraging 400 others to join her on July 14th, 1518 in Strasbourg, France near the border of Germany.

For the Black Plague, fear was the internal force that shook communities to continue with devoted prayer and heightened stress. This plague remained in modern history books for the devastating population decline the world experienced.

Spanish Flu Art: The Last Moments

Political uncertainty, atrocities of WWI, and collective absurdity were the ingredients that accompanied the theme of the 1918 Spanish Flu (controversially named), the deadliest modern pandemic with over 50 million victims.

It appears, however, that the onslaught of the virus was overshadowed by the current events of the time. In today’s realm, the early 20th-century virus hadn’t been a notable topic that rang in our collective memory.

Not until the current pandemic did most of us decide to brush up on the effects of the previous pandemic. What we found was that it was the second and third waves of influenza that had hit the hardest, meanwhile, we are still experiencing our first battle with coronavirus.

Artists expanded through their confusion, a character of the zeitgeist, erupting with Dadaism and abstract art forms.

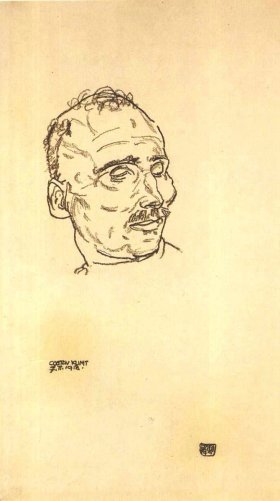

There is some art to memorialize the flu, they are portraits and self-portraits from young artist Egon Schiele of those in their last moments or resting on their death bed, like Gustav Klimt, who died from complications of the virus. Schiele even detailed his pregnant wife, Edith, days before her and their unborn child’s death from influenza. Egon Schiele would die just a few days afterward at 28 years old unable to finish The Family, a haunting reminder of the imagined life he would never live out.

Edvard Munch, famous for The Scream paints himself in Self-Portrait With the Spanish Flu, an open mouth, no eye depiction surrounded in light orange tones. Munch’s survival of the flu leads him to paint Self-Portrait After the Spanish Flu, a severely disturbing portrait of darker facial tones but still accompanied with bright window light signifying hope.

The Spanish Flu did not provide any concrete iconography for future generations to ruminate over or plant popular memorials for the victims. Rather, we remember the end of the 1910s by the aftermath of a horrific first world war, a death toll that includes victims of the flu.

Confusion and overshadowing integrated these influenza nightmares to seemingly long-ago periods that may confirm why many of us were wildly unfamiliar with that pandemic. Can our present actions and created art warn future generations of battle with the disease, or will we remain as feverish as the Spanish Flu?

Coronavirus Art: Entering a New World

We encountered most COVID-related art through internet platforms and neighborhood murals. The WWW and the outdoors were the only places to visit during a stay at home order. While the internet art fads seemed to change daily, there were a few that made a lasting impression.

Remembering just a few months ago can issue out a headache but the milestones of disaster tend to be dated by; Australian bushfires in January, Brexit, impeachment trials of Trump, death of Kobe Bryant, locust swarms, the brief news craze of murder hornets, American tensions with Iran, death of George Floyd and following protests, and of course our global health crisis and lockdowns. There will be little surprise when artists or anyone decide not to make sense of anything again.

Dark humor spreads rapidly through Twitter and it wasn’t long before a meme defined the new year. Originally posted on Youtube in 2015, the Ghanian dancing pallbearers quickly became synonyms with fails edited for TikTok with an EDM soundtrack in early 2020. Even Trump retweeted an edited version of Biden’s campaign as the coffin. Yet when circumstances became too serious to joke about, the dancing pallbearer meme slowly dissipated into the internet sphere.

Over the last decades, astonishing murals have popped up on tunnels, coffee-shop walls, or on the brick facades of city apartments. Since the pandemic, art has shifted to the global theme of humans, doctors, and iconic figures like the Statue of Liberty wearing face masks for our “new normal.” Its art made for the living by the living.

Biking through the city and lush Greenbelt of Harrisburg I hadn’t noticed pop-up dedications for the victims of COVID-19. Does this lack of tribunal art for those lost mean we aren’t afraid of death like epochs of disease before?

Vacant streets of overpopulated cities are the eerie reminder that this lockdown happened within weeks (for some of us, months) of the first report without most of us expecting it. Photographers took this opportunity to shoot the streets of Tokyo, Chicago, or markets in India without fresh footsteps or shoppers, an easily mistaken post-apocalyptic photo for future aliens.

Along with empty streets came empty shelves, the supermarkets across the nation became sparse while the assholes who bought in major bulk became numerous. I’d run into those at the post office shipping toilet paper to Florida and bonded with women in the desolate oatmeal aisle. My favorite was the sociology threads on Twitter examining the products leftover even after panic shopping, cauliflower pizza crusts, and plant-based meats appear to be the last kid picked on the dodge ball team.

George Floyd/ BLM Art: Gathering for Change

SAY THEIR NAMES; Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, Trayvon Martin, Breonna Taylor, Philando Castile, Marcus Brown, Eric Garner, Alton Sterling, John Crawford III, Ezell Ford, Dante Parker, Michelle Cusseaux, Laquan McDonald, George Mann, Tanisha Anderson, Akai Gurley, Rumain Brisbon, Jerame Reid, Matthew Ajibade, Frank Smart, Natasha Mckenna, Tony Robinson, Anthony Hill, Mya Hall, Philip White, Eric Harris, Walter Scott, William Chapman II, Alexia Christian, Brendon Glenn, Victor Manuel Larosa, Jonathon Sanders, Freddie Blue, Joseph Mann, Savado Ellswood, Albert Jospeh Davis, Darrius Stewart, Billy Ray Davis, Samuel Dubose, Michael Sabbie, Brian Keith Day, Christian Taylor, Troy Robinson, Asshams Pharoah Manley, Felix Kumi, Keith Harrison Mcleod, Junior Prosper, Lamontez Jones, Paterson Brown, Dominic Hutchinson, Anthony Ashford, Alonzo Smith, Tyree Crawford, India Kager, La’vante Biggs, Michael Lee Marshall, Jamar Clark, Richard Perkins, Nathaniel Harris Pickett, Benni Lee Tignor, Miguel Espinal, Michael Noel, Kevin Matthews, Bettie Jones, Quintonio LeGrier, Keith Childress Jr, Janet Wilson, Randy Nelson, Antoine Scott, Wendell Celestine, David Joseph, Calin Roquemore, Dyzhawn Perkins, Christopher Davis, Marco Loud, Peter Gaines, Torrey Robinson, Darius Robinson, Kevin Hicks, Mary Truxillo, Demarcus Semer, Willie Tillman, Terril Thomas, Sylville Smith, Terrence Crutcher, Paul O’Neal, Alteria Woods, Jordan Edwards, Aaron Bailey, Ronell Foster, Stephon Clark, Antwon Rose III, Botham Jean, Pamela Turner, Dominique Clayton, Atatiana Jefferson, Christopher Whitfield, Christopher McCorvey, Eric Reason, Michael Lorenzo Dean, George Floyd.

What makes this revolutionary art different from plagues and pandemics is the immediate notion that a specific type of human life is targeted, the obvious case, being black. An entire community living in fear of unjustified death amongst a community most admittedly ignorant to police brutality crimes.

The parallels of mass protest can be tied to the manic dancing with the collective stress of isolation, false reporting, mistreatment, and murder of black people by “protective” services.

Marching or dancing together as a collective is a ritual to mourn and an act for change.

The names of victims listed above or phrases from the movement; “Black Lives Matter,” “I Can’t Breathe,” “No Justice, No Peace,” or “Defund The Police” can be heard and read from protestors’ cardboard signs. Many city windows are covered in these proclamations, an alternative for those still cautious of joining massive crowds.

Consistency of human expression through art in grief, stress, and assembling sense seem to outpour through the same mediums of gathering by dance, march, or paint.

In a time where distance is key to many’s survival our reward, in safe time, will be to convene again in joyous ritual. Hopefully appreciating and witnessing the subtitles of living; watching a dancer’s skin breathe and stretch, clapping together when a waiter drops a platter of water glasses or hugging a person for the first time without virus in our minds. More so, hopefully, we can gather where nobody feels an inevitable encounter from police based on the color of their skin.

Resources/ Further Reading:

Black Death:

Smithsonian- Dancing Mania in Germany

Spanish Flu:

Time – How Artists Tried to Make Sense of the World

Black Lives Matter: